Three decades in Southern California’s food service threw me into a crucible—hot, cramped, relentless. Kitchens taught lessons no school could: survival under pressure, loyalty under fire. Whether slinging 500 fine-dining plates on a Friday night or 300 grilled chickens for the Sunday church crowd, every restaurant had its own rhythm. Each brigade was a family—unique, invaluable, irreplaceable—forged in sweat and chaos.

Work ethic, loyalty, dependability: these were non-negotiable. You showed up, you worked, you didn’t crack. Huge egos, deep insecurities, high-functioning alcoholism? Just tools to cope with the madness. I’d tell newbies, “Get out while you can,” but most stayed, hooked by pride or trapped by need. The kitchen’s siren call was different for everyone, but it sang to us all.

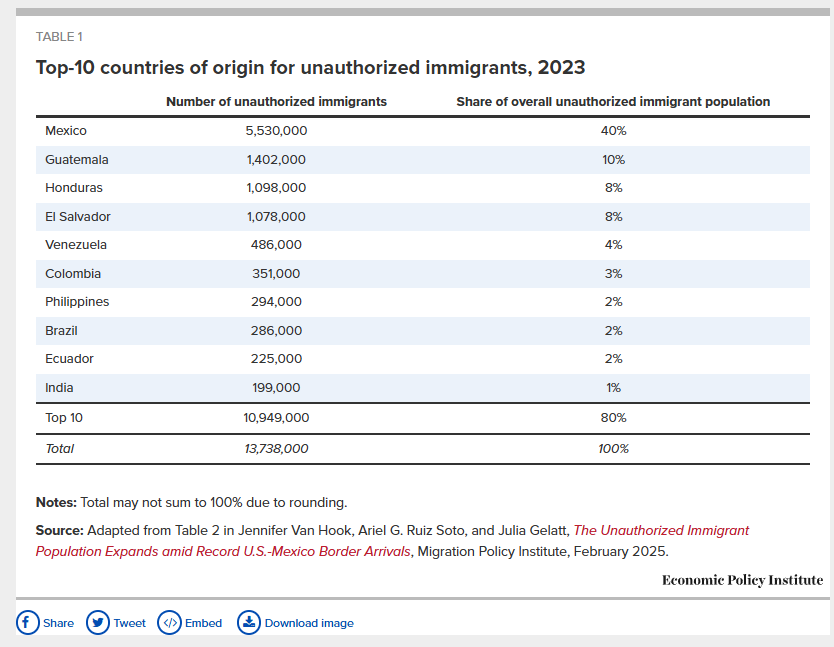

Many coworkers were undocumented, labeled “illegal aliens” by the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform Act. “Undocumented” is a polite dodge—every one I hired had papers: Social Security cards, driver’s licenses, green cards. All fake. HR’s mantra, drilled into us at day-long compliance sessions, was clear: “Report the information, don’t verify it.” We played the game, knowing the truth. In the ‘90s and ‘00s, kitchens buzzed with folks from Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador—their origins spiced our food, our culture. In LA’s Frogtown, I lived around the corner from Won’s Tacos, where Korean tacos and teriyaki burritos were born. Fusion before it had a name, proof of cultures colliding in delicious ways.

But today’s newcomers—Haitians, Venezuelans, Somalis—bring new tensions. I saw it in the kitchen: longtime cooks grumbled about “outsiders” taking shifts, while newbies hustled to prove their worth. Why blame law enforcement for enforcing a broken system? The real question is: What happened? How did we get here, simmering in this stew of our own making?

I worked with incredible people, many here illegally, cashing paychecks they weren’t supposed to earn. Take Ana, a cashier in 2004 at a chicken chain. She was the unit’s backbone—fast, precise, unflappable. Every November, she’d head to Mexico, returning in February as Maria, then Rosa. Jose, the grill guy, came back as Juan one year. HR shrugged; it was routine. These weren’t just workers—they were innovators. A Guatemalan line cook taught me a lime-chili salsa that had customers begging for the recipe. A Salvadoran dishwasher’s mole became a staff meal legend. Their origins fueled our menus, our community.

Outside the kitchen, though, their lives were shadowed. Most worked double shifts—8 hours at Pollo Loco, then 8 more at another spot, biking miles between. I lived it too: running a kitchen in DTLA, I worked 7 a.m. to midnight, Monday through Friday, sleeping in my car during lunch breaks. Weekends were for side hustles. I barely saw my kids awake; my wife knew me as a stranger. The grind was brutal, but the pride was real. Every plate I served—fine dining, fast casual, greasy spoon—I was proud of the food.

My British cousin learned the stakes in ‘82. He arrived on a tourist visa, his accent charming clients at an ad agency. Life was golden until a Baja day trip. At the border, his paycheck stub betrayed him. Visa valid, work illegal. He was on a plane to Birmingham the next morning, California dream shattered. It was a lesson in status’s fragility, echoed in countless coworkers’ lives.

Kitchens were melting pots—of people, ideas, flavors. In the ‘90s, LA’s food scene crackled. At one joint, a Mexican chef and a Korean line cook sparred over whose kimchi-jalapeño burger was better. Customers ate it up. We spoke Spanglish—orders shouted in English, Spanish, kitchen shorthand. We were building community, “all getting along,” as the post-’92 riots mantra went.

But beneath the harmony was a facade. Immigration raids, border checks, fake IDs—they loomed like storm clouds. I remember Fermin, a line cook, vanishing after a traffic stop. He was back a month later, new name, same gold tooth. We didn’t ask questions; we needed him on the line.

This isn’t just a kitchen story—it’s America’s. We’ve embraced undocumented labor’s benefits while dodging its costs. Restaurants, farms, hospitals, homes—they thrive on this hustle. A dishwasher worked 12 hours, then moonlighted as a cleaner. A prep cook sent every dollar to her kids in Honduras. Their grind was one most Americans couldn’t stomach, yet we leaned on them, expected them, demanded them.

What happened? America outsourced blue-collar work and insourced the grind. We hired nannies who knew our kids better than us, gardeners with gate keys, nurses who held our loved ones’ hands in their final moments. We didn’t just hire them; we wove them into our lives. Yet now we face the question: who’s deportable? The “bad hombres” or folks like Ana, cycling names to stay afloat? The system’s a mess we built, fueled by entitlement and dependence.

I left corporate in ‘97, entering a world of commodity labor. Restaurants stopped engraving name tags; workers swapped documents at will. Ana’s annual Mexico trips were clockwork, each return a new identity. Was it a critique of her? Hell no—she worked harder than most. But when does one story become a million? Ten million? Are they all as dedicated? Many are, but not all. That’s the rub.

The past fours years, though, were a turning point. Illegals became global, with new faces from Asia, Africa, the Middle East. Now, Somalis and Venezuelans competed with established immigrants. Equally illegal in undocumented status, the new arrivals sparked friction and created division in underground communities.

Longtime workers felt squeezed, shifts tighter, tensions higher. The system, already strained, groaned under the weight. In 2004, as GM at a chicken chain, I managed a revolving door of names—Ana to Maria, Jose to Juan. It wasn’t deceit; it was survival.

The cultural fusion was magic. Spanglish evolved into a polyglot slang—Spanish, English, Tagalog, French. We were inventing, not just cooking. But the shadow of status lingered. One night, a raid hit a nearby diner. Half the kitchen vanished. The owner scrambled, hiring anyone with papers—real or not. Chaos, but normal. We’d adapted to a broken system.

America’s addiction runs deep. We’ve outsourced construction, agriculture, childcare, healthcare. How many of us hired a guy at Home Depot for a dirty job? A nanny who became family? A gardener who knew our backyard better than we did? We’re not just complicit—we’re dependent. Our economy hums on this labor, yet we debate deportation like it’s simple. Are we uprooting criminals or longtime residents who’ve lived in the shadows for decades?

The unwritten contract was this: you work, we look away. It worked until it didn’t. By the 2000s, the labor black market was entrenched. Restaurants, car washes, farms—they ran on it. I saw it in ‘03 at a burger joint: a cook, Carlos, was picked up in a raid. He returned as Miguel, no questions asked. We needed him flipping patties. But the cracks were showing. New arrivals flooded in, global crises pushing them here and open borders letting them in. The system, built on winks and nods, couldn’t handle the scale.

What happened? We built a house of cards. Americans stopped doing “jobs Americans won’t do”—a phrase that’s both truth and excuse. Our welcome mat, symbolized by a statue in a harbor, got trampled. We created a labor market where names change like shifts, where Ana becomes Maria, Jose becomes Juan, and the hustle never stops. But the hustle’s not universal. For every Ana, there’s someone gaming the system, and that’s where the debate ignites.

In ‘99, I ran a kitchen where a raid left us short-staffed for weeks. We scrambled, hiring unvetted workers, papers be damned. Asking a teenage white cashier to empty all of the trash cans prompted her common reply “That’s a Mexican job.”

It was survival, but it exposed the fragility. By 2025, the global mix—Haitians, Syrians, Hondurans—added complexity. Tensions flared. A Mexican cook I knew, 20 years in the U.S., complained about “new guys” undercutting wages. The unwritten contract was fraying.

The pride of food service never faded. I loved every concept—greasy spoons, upscale bistros. But the paradox stung. We celebrated diversity—flavors, stories, languages—while ignoring the legal tightrope our coworker’s walked. Post-shift beers were for laughing about botched orders, not status. Yet the threat was real. In ‘03, a raid hit during a lunch rush. Two cooks gone. We limped through service, but it wasn’t the same.

What happened? We got comfortable with hypocrisy. We built a system that thrives on undocumented labor while pretending it doesn’t. Now, the veil’s off, and we’re left with hard questions. Who stays? Who goes? How do we balance humanity with law? The kitchen taught me pride, but also truth: this mess is ours, and it’s time to own it.

Enjoy your taco,

Ric

Enjoyed this raw take? Subscribe to Compass Star Wordsmith for more on culture, work, and life. Paid subscribers get exclusive content and custom leathercraft perks!

Growing up in Northern Michigan and working in restaurants up there, it was not like that at all. Southern Michigan farms had their migrant labor living quarters, but those closed up with the invention of better farm equipment. It's interesting how so many places did weave the undocumented worker into their rates. It's also not a great look for how much these businesses exploit these workers to keep their rates down.

I guess the question to be asked is this - are the current crop of illegals as diligent in their work habits as the old bunch. Have they become like the current crop of millennials who feel to entitled to actually do things to earn their paycheck.

Do Venezuelans today work as hard as Mexicans did 20+ years ago? It shouldn’t make a difference, illegal is illegal, but I wonder if that is part of the battle going on.