The introduction of horses in the firehouse was itself a controversial innovation that had been fought tooth-and-nail by traditionalists.

There’s no stopping revolutions, especially ones that turn victims into survivors. The march of Technology (nee Industry) is relentless, repetitive, and remorseless. It stops at nothing as it consumes everything. It eats the past and shits the future. And here in the present, we live the paradox we protest. We hate The Robot.

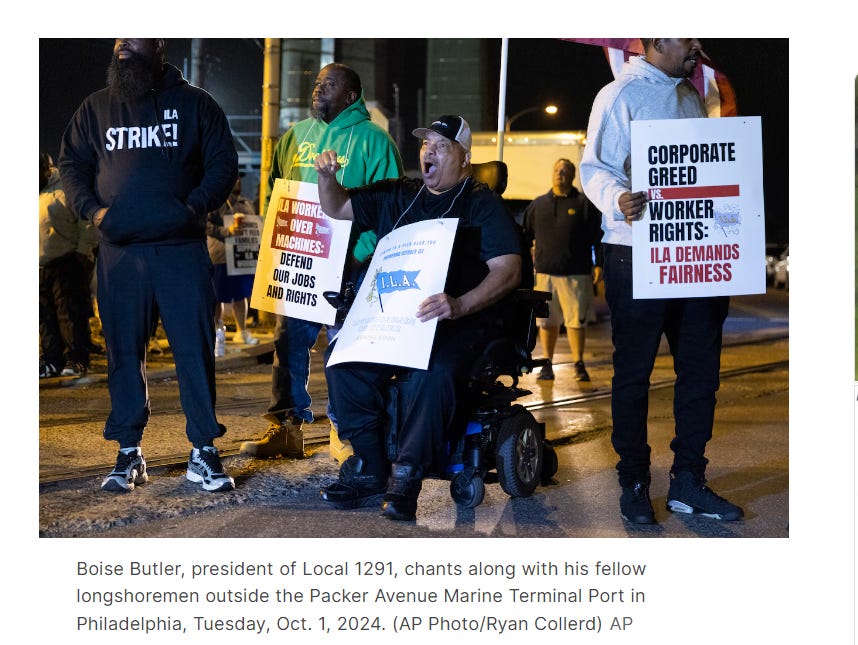

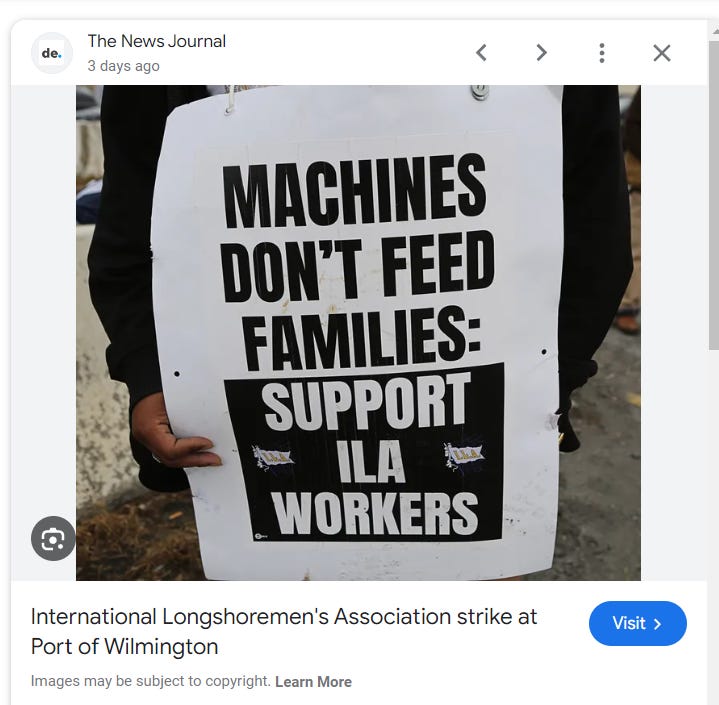

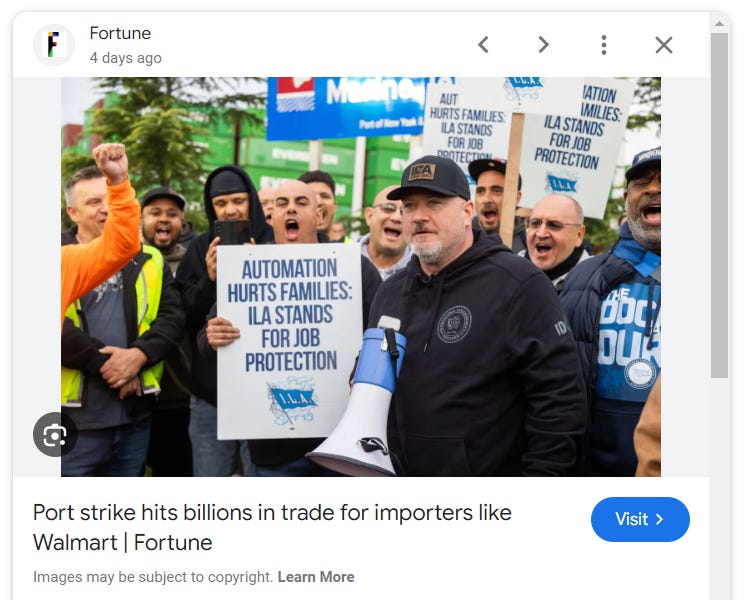

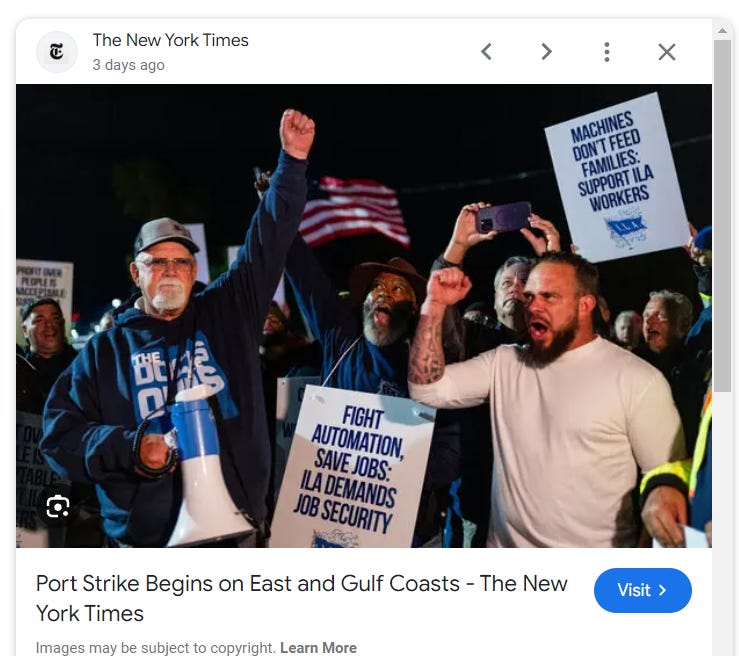

I posted a Notes last week with a photo showing the overall sentiment of the International Longshoremen's Association strike. I found other images that illustrate this stage of the revolution in full-swing. Carefully note the blue and white apparatus commonly called a Bullhorn. Technically, it’s a Megaphone. Ironically, it’s been automated. They’re not the only union resisting Automation.

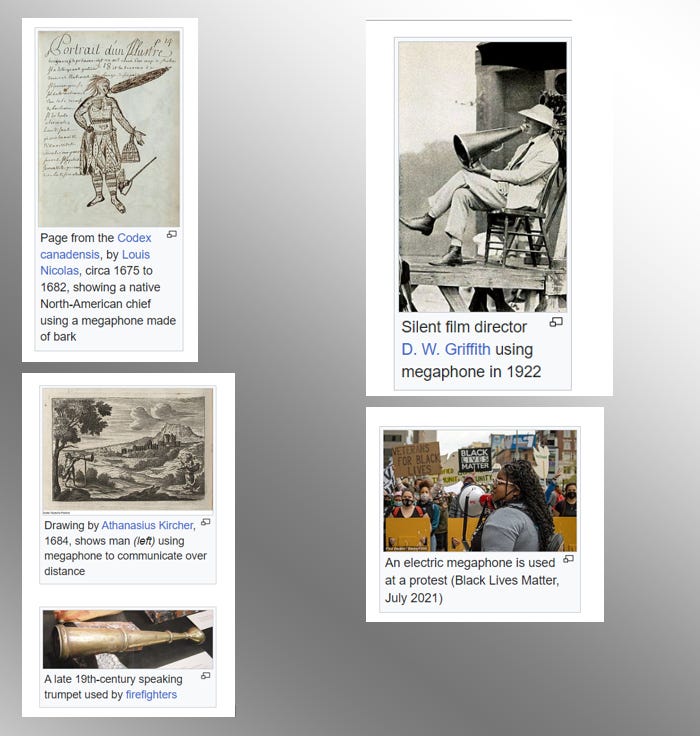

Here’s a pictorial history of the bullhorn. Make what you will of Black Lives Matter protesters using the latest model of the same tool the director of Birth of a Nation used (barely a century before). Automation did that. Living the protest signs slogan would have us all holding “a megaphone of bark”. Irony indeed!

Electric Megaphone - Exhibit A for Automation

An electric megaphone is a handheld public address system, an electronic device that amplifies the human voice like an acoustic megaphone, using electric power. It consists of a microphone to convert soundwaves into an electrical audio signal, an amplifier powered by a battery to increase the power of the audio signal, and a loudspeaker to convert the audio signal to sound waves again. Although slightly heavier than acoustic megaphones, electric megaphones can amplify the voice to a higher level, to over 90 dB. They have replaced acoustic megaphones in most applications, and are generally used to address congregations of people wherever stationary public address systems are not available; at outdoor sporting events, movie sets, political rallies, and street demonstrations.

Although electronic public address systems have existed since vacuum tube amplifiers were developed in the early 1920s, vacuum tube versions were too heavy to be portable. Practical portable electric megaphones had to await the development of microelectronics which followed the invention of the transistor in 1947. In 1954, TOA Corporation developed the EM-202, the world's first transistorized megaphone.[5]

Gas Power Kills Horsepower

Unintended consequences prove widely consequential, and even more fascinating to study. Resistance to Automation is nothing new. The history of the Teamsters Union, in particular, is rife with rage against the machine.

On December 20, 1922, the sound of restless neighs and the stamping of hooves echoed in the streets of Brooklyn Heights as Fire Engine 205’s finest strained against their hitches, eager to charge into the cold winter morning. Assistant Fire Chief Joseph “Smokey Joe” Martin rang the alarm bell at the station, signaling the company’s “first whip” John J. Foster to climb aboard the engine, pick up the reins and drive his eager team of horses out into the streets of New York City.

But there was no fire. The team was heading towards a ceremony at Brooklyn Borough Hall, where a sleek new motorized engine was waiting to formally replace the horse-drawn engine.

The echoes of past protests ring hollow for modern union traditionalists, and it seems that striking against Automation is misguided at its core and futile in its purpose. But labor is not alone in their denial. By rejecting the advancement of technology, they may be going the way of the buggy-whip makers. Also see Kodak. And Radio Shack.

Consider the following facts on the ground at the turn of the 20th century, that literally, eerily foreshadow our current state of commerce and pollution

In 1908, New York’s 120,000 horses produced a pungent 60,000 gallons of urine and 2.5 million pounds of manure every day on the city’s streets.

The number of city horses swelled as did the peripheral industries that supported them: teamsters, streetcar operators, carriage manufacturers, groomers, coachmen, feed merchants, saddlers, stable keepers, wheelwrights, farriers, blacksmiths, buggy whip makers, veterinarians, horse breeders, street cleaners, and the farmers who grew grain and hay.

It’s difficult to overestimate the degree to which the American economy and broader society revolved around horses. As one historian has commented, “every family in the United States in 1870 was directly or indirectly dependent on the horse.” In rural areas, farmers prospered in no small measure by growing hay to feed the nation’s 8.6 million horses, or one horse for every five people. (And each horse ate a lot more than a person.)

In urban areas, the reliance was even more striking. This dependence hit home in the fall of 1872, when a serious strain of horse flu spread throughout the northeast U.S. and for some weeks horses could not be used. City life ground to a halt as streetcars stopped running, urban goods stopped moving, and construction sites stopped operating. Consumers suddenly confronted shortages when buying groceries. Perhaps even more disturbing for some, saloons ran out of beer. There was nothing like the horses’ illness to demonstrate that such a large part of the American economy and its jobs revolved around horses.

Now & Forever No Automation No Fire Horse

The Addition of the Fire Horse

Originally man-powered fire engines (hand pumpers) were manned by volunteers that both hauled the apparatus to the fire and then manned the fire brakes (pump lever handles) to generate the pressure to pump water on the fire. It was a point of pride as to which a fire company could get their fire engine to the scene first and pump the most water. This process required large numbers of volunteers or drafted citizens to help keep up the strokes of the pump going during a fire. The first use of fire horses was not easily accepted, and many firefighters resented and protested their use. One of the first recorded purchases of a fire horse was by the New York Mutual Hook and Ladder Company No. 1 in 1832. The reason they acquired a horse to pull their engine was presumed to be related to a yellow fever epidemic that created a shortage of manpower. As is the case for many early adopters of innovation, this move was not well received by the other fire companies in the area.

Undiscovered professions sprout from Automation Revolutions. Prior to the steam pumper, fire departments were volunteer organizations. Just a bunch of dedicated yahoo’s pulling and pumping for the betterment of society. But now, the firehouse is a brigade - with ranks defining duties. Think Fire Apparatus Engineer.

Here’s more fighting the good fight, and again against Automation. Again. Always, it seems. They fought the horse. They protested steam-power. But they eventually adapted, adopted, adjusted. Some would say they flourished. And now, back to No Automation - No Robots.

And here is IRL’s current President leading the charge against Automation. Again, with a product of Automation in his right hand, and other protestors utilizing Automated tools. But striking in America started long before America did. Did you know the Poles protested the English Colonial Rule in 1619? Yup.

Polish artisans strike for the right to vote, Jamestown, Virginia, 1619

In 1619, the Governor of Virginia, Sir George Yeardley, returned from England with instructions to form the first elected legislative body in colonial America. The new assembly was meant to give “free liberty” to all men through “freely elected” representatives that would make laws for the land.

Except suffrage was not extended to all of the colonists, not even all of the men, not even all of the white men, but only English, landowning men above the age of sixteen.

Though the specifics of what occurred next may be lost to history, Virginia Company records suggest that Polish workers went on strike demanding suffrage. According to court records dated 21 July 1619: “Upon some dispute of the Polonians resident in Virginia, it was now agreed (notwithstanding any former order to the country) that they shallbe enfranchized, and made as free as any inhabitant there whatsoever: And because their skill in making pitch & tarr and soap-ashes shall not dye with them, it is agreed that some young men, shallbe put unto them to learne their skill & knowledge therein for the benefitt of the Country hereafter.”

I watched a documentary about the contributions of European Poles in Jamestown. It was eye-opening because, as we’ve learned, they didn’t teach us crap in public schools. Or actually, maybe it was all crap!

This is an old-school doc, with no flash or bang. Just some professors telling the story. Seems the Poles were a religiously-tolerant people at the apex of their power at the time, and their craftsmen and artisans were highly sought after.

It’s not Automation, per se. It’s the fear of Replacement. Most of the Union Workers in this post are proud strong Americans, fearful of loss. Afraid that circumstances beyond their control will dictate their future. Join the fucking club.

African Chattel Slavery was the Human Industrial Complex of 1619. It replaced Indentured Servitude, which proved inefficient and unsustainable. Given the choice of Freedom, most Slaves rebelled. How American. Not perfect. Just done.

Fire made us Human. The Wheel made us mobile. Slavery made us disposable. Automation can make us replaceable. But it does not have to. To be replaced is a choice. And most Americans choose to protest the subjugation of our Freedom.

In conclusion . . .

Make The Robot pay taxes. Make the Company pay taxes. But the right kind of taxes. Labor Unions and Company Management should welcome Automation for several mutually beneficial reasons. After all, humans have disrupted the status quo since fire and the wheel. Every Revolution advances the human experience.

Efforts dating back to the Industrial Revolution to stop automation have often been unsuccessful, Brynjolfsson said.

Knowing that this is, in fact, an old dilemma and not a new problem makes the pain even worse. Man has always feared the new and unknown and then conquered it and made it our own. We’ve done it again and again.

Will we ever get over the fear of AI?

"The fear will eventually subside to caution, and then collaboration, like most things as we learn to live side by side and augment our lives with the power of AI," says Loops co-founder, Scott Morrison.

Sometimes, we find some comfort in the inevitable. Whether we like it or not, artificial intelligence is here to stay, already too ingrained in our everyday jobs and lives to simply cut it out.

Of course MIT is full on The Robot Cheerleader. Low taxes on Robots to start, and then lower them even more. Automation is woven so completely in Human DNA it’s too late to stop. But we can take stock of where it is now, where WE want it to go, and how to educate, literate, liberate those among us wary of Automation. We cannot win this fight. We cannot control innovation - which is just thought.

As the former CEO of McDonald’s USA famously quipped, “[i]t’s cheaper to buy a $35,000 robotic arm than it is to hire an employee who’s inefficient making $15 an hour bagging French fries. . . .” McDonald’s is now expanding its use of automated cashiers throughout the United States and in other countries.

We have choices. Let’s employ them. I’ll take a self-driving car any day. Let’s make The Robot our chauffeur, not our master.

Enjoy the protest playlist,

I hope you know the care in my heart for all of my readers,

Ric

In 1870, 75% of the US Labor force was egaged in producing food. Through automation, today thiis is two percent.

]We're sttill heree.

Wonderful context. I should note that longshoremen used to use handtrucks and manual labor to unload ships. Now they use cranes to remove containers. .