We never stopped to sightsee. Not once. From Boston to Rancho Cucamonga, three thousand one hundred and eighty-three miles of America blurred by. I rode shotgun with a phone and a mission: capture every barn I could without pulling over.

Mission Purpose was not clear at first. This was a full-blown all-the-fricking-way across the whole-dang-continent of North America. Not solo. The Youngest Daughter and Lucy The Doodle-Dog were coming home to LA, in her car with her rules and her playlist. The ground rules were clear, concise, and complete.

She knew that her Dad had a certain set of skills perfectly suited to crossing 14 states in six days - 125+ hours, four hotels, and three family stops in a sedan together without internecine warfare. Do we get a family badge for that?

As the miles clicked by, one type of structure kept making appearances in all of its wondrous and wonderful shapes. All in the pursuit of one job. My Mission.

The Barn.

What is a barn?

A barn is a working memory, built with intention and used until it's no longer needed. It holds tools, animals, harvests — but also time, weather, and stories passed without words. It doesn’t perform; it just does. A barn ages without apology, collapsing not from failure but from having served its purpose. It is proof that usefulness can be quiet, and dignity can be unpainted.

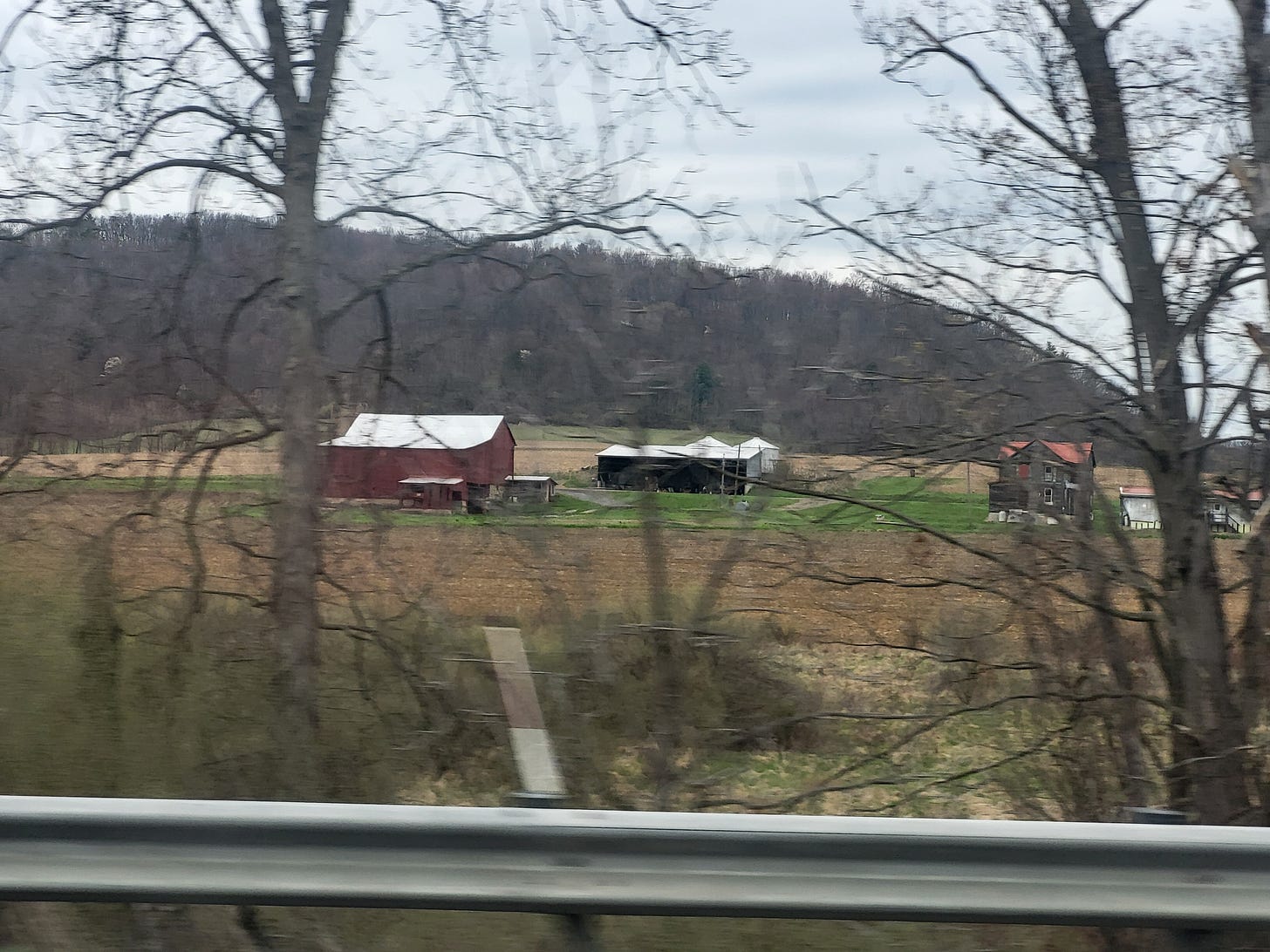

Rolling through recently harvested and yet unplowed fields exposed the usually unseen utopias of farm life. Silos. Sprinklers. Barns. Houses. Trailers. Tractors.

A complex of structures concentrated at the heart of a patch of land, typically hidden by cornstalks over 10-feet tall are now revealed in their intermezzo of seasons - human, beast, soil, and machine - all requiring a respite, a recharge, a renewal.

Like the ground they plough and pluck, the farmer follows the sun, and so did we. Or maybe, we just chased the sun. Once freed from daily conventions and consumer tasks unnecessary while road-trip car-living, human and dog are reduced to satisfying simple needs.

Breaks came about every 200 miles or so - gas, pee, eat, dog. Back on the road averaging around 500 miles a day, one hotel to the next. Once we got out of New York, the vastness spread out before us. Post-harvest and pre-planting provided usually unseen farmland, grain silos piercing the fallow fields, clearly the hub of humanity.

Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois are indistinguishable without a Google map. The Daughter was “I’m Bored” from border to border. The barns were coming too frequent to photo and the car was going too fast to complain. Yet I soldiered on in duty to dignity, barn after barn. These images were taken at speed. The Daughters sighs duly noted and notwithstanding.

On the way to Manson, Iowa — population barely scratching four digits — the barns came thick. Every few miles, another one: some still standing proud, others giving way. There was one in particular — tilted so far sideways it looked like it was bowing to the road. I didn’t get the shot. But I remember it clearer than some of the ones I did.

It hit me: barns don’t get torn down. They just collapse.

Not all at once. It’s a slow unraveling. The roof bows in, a board pulls loose, the siding curls away from the frame like it’s tired of holding on. The door sags off one hinge. Eventually the whole structure just… gives. Not from neglect, but from long use. They’re built to serve, not to shine.

You don’t see “For Sale” signs nailed to barns. No liquidation banners. No wrecking crews. They’re used until they’re not. And then they wait. They wait until time or wind or a hard winter tips the balance and down they go, piece by piece, quietly. As if even in collapse, they don’t want to cause a scene.

There’s something noble about that. And about the Farmers that work the land.

By the time we crossed into Iowa, I was fully invested. This was no longer just a distraction to pass the hours — it was the throughline. The barns were the story. Every time one appeared, I’d lean up, swipe open the camera, and try to time the shot through a bug-smeared window while flying down the highway in the passenger seat. No slowing down. No pullovers. Snap. Gone.

Some came out crooked or blurry or half-cut by a side mirror. Others landed perfectly — light hitting just right, composition clean. But it wasn’t about perfection. These barns weren’t trying to impress. They weren’t there to be photographed. They just were. The camera either caught them or didn’t. They didn’t care.

Some were clearly still in use. Others hadn’t seen a tractor in decades. But even the ones on their last leg — maybe especially those — felt like monuments. Not to nostalgia, but to labor. These weren’t selfie-ready ruins. These were practical, purposeful, aging workhorses.

And just like that, I found a metaphor riding shotgun.

We pushed west, and the barns came with us. Even as the farmland gave way to pastureland, then prairie, then sparse desert, they kept appearing. Not as frequently — but still there. Holding their shape against the elements. Out here, they didn’t look like New England or Midwestern barns. These were practical structures, built for wind and sun more than rain and snow. High Plains barns — Colorado, Northern New Mexico — felt leaner, harder. More rib than muscle.

And then, just out of Farmington New Mexico and south of Shiprock, I started to see something different. Smaller, humbler, but unmistakably barn in spirit — timber frames lashed together, stones stacked with intention, simple lean-tos sharing space with hogans. Shelter shaped by the land itself. Not cut from blueprints, but carved out of memory and need.

They weren’t always photogenic. But they hit harder.

This was no longer just a visual motif. It was a language — adapted, regionalized, still telling the same story. We shelter what we value. Our animals, our tools, our food, our families. Barns and hogans both honor that instinct — to protect, to preserve, to endure. They’re shaped by different histories, different hands. But they answer the same question: how do we keep what matters safe?

Even in that dry, sunburnt expanse, the metaphor held. The barn doesn’t belong to one people or one place. It’s a structure of intention. It rises out of the dirt because something needed doing. And it stays, long after it’s done.

Out here, the barns weren’t decaying so much as weathered into wisdom. They didn't sag like their northern cousins. They settled — like old stories told slow, worn down to just the bones.

Eventually, the barns thinned out. Somewhere past Kingman, they started to disappear. The land turned scrubby, the towns dustier, the space between utility and nostalgia grew wider. We were no longer in barn country.

The landscape flattened again, but this time it was different. No fence lines. No corrals. No rusting tractors resting in the shade. Just signs for gas, exotic jerky, fast food, billboards screaming about accident attorneys and outlet malls.

By the time we rolled into Rancho Cucamonga, it was all cul-de-sacs and Costco plazas. Vinyl-sided sameness. Shiny SUVs and manicured rockscapes where a front yard might have been.

No barns in sight.

And suddenly it felt like something was missing — some quiet anchor that had been riding alongside us the whole time. Not loud. Not attention-seeking. Just there.

The barn had become a kind of companion. A mile-marker of meaning. A structure that didn’t demand your gaze, but offered something real if you happened to glance its way.

Now, surrounded by stucco and speed bumps, the absence was loud.

I thought about the barns we passed — their posture, their decay, their endurance. None of them asked to be remembered. They weren’t curated, museum’d, or archived. They just lived until they couldn’t. And in doing so, they left something behind.

There’s a lesson in that.

We build things — structures, families, selves — not to last forever, but to serve a purpose. To house what matters. To hold strong through storms, wear, change. And when our purpose shifts, or fades, or finishes... maybe collapse isn’t failure. Maybe it’s just another form of return.

Maybe we don’t need to be shiny to be seen. Maybe we just need to stand long enough for someone passing by at 80 miles an hour to look out the window and say, “That mattered.”

Thanks for riding along, many more barns yet to see.

Go find your barn,

Ric

Trick Shots Too!

Check out a fun road trip playlist.

That was a hell of an idea for an essay…something worth spending time reading.

Great photos and commentary, Ric. You should package it as a little book—kdp.amazon.com. No setup fees. They make money on the millions you'd sell! :-) In my younger years, I made 3-1/2 roundtrips across the country, first solo from NYC, then later to and from Boston with my second (or first, depending on who's talking) in command. Five hundred miles a day, but always a timeout in Kansas visit my parents. Say hi to the youngest.